In June, 2009 I successfully defended my thesis and was awarded a doctorate of computer science by the University of Iowa. What followed were some of the most productive years of my professional career. I designed, programmed, project managed and was principal investigator on:

MARS: Military Advanced Real-time Simulator (2009)

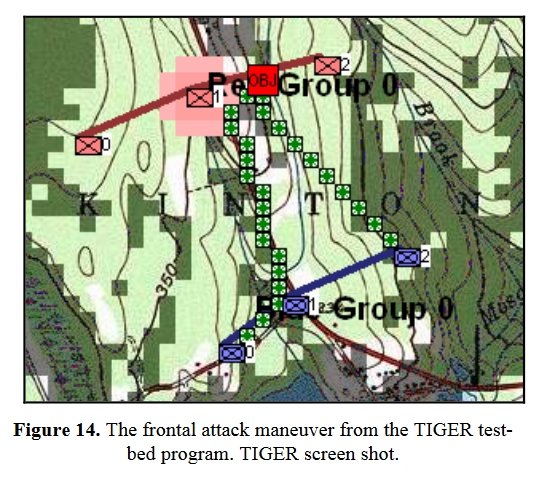

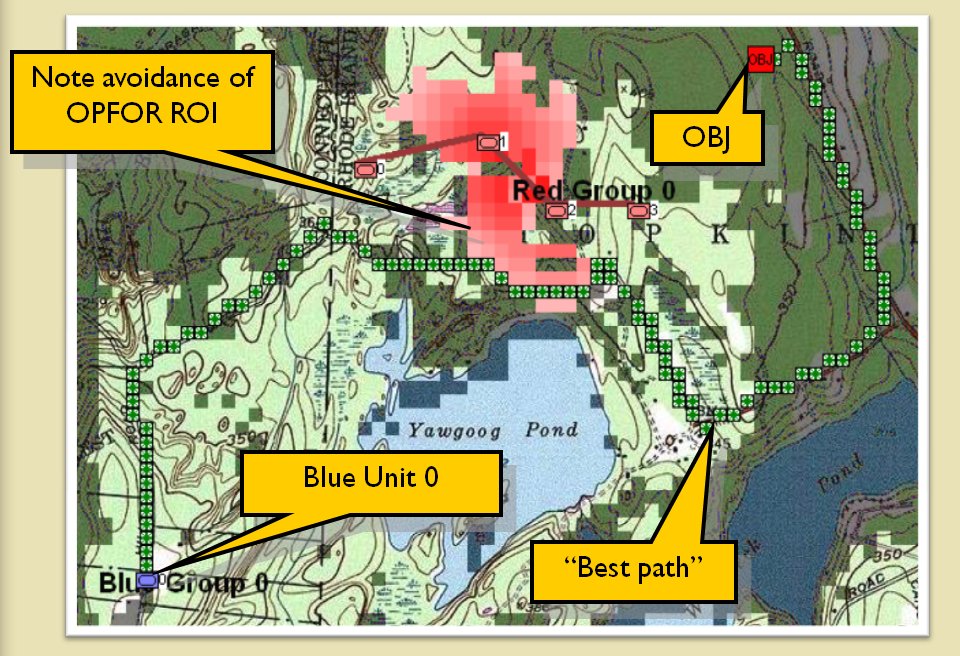

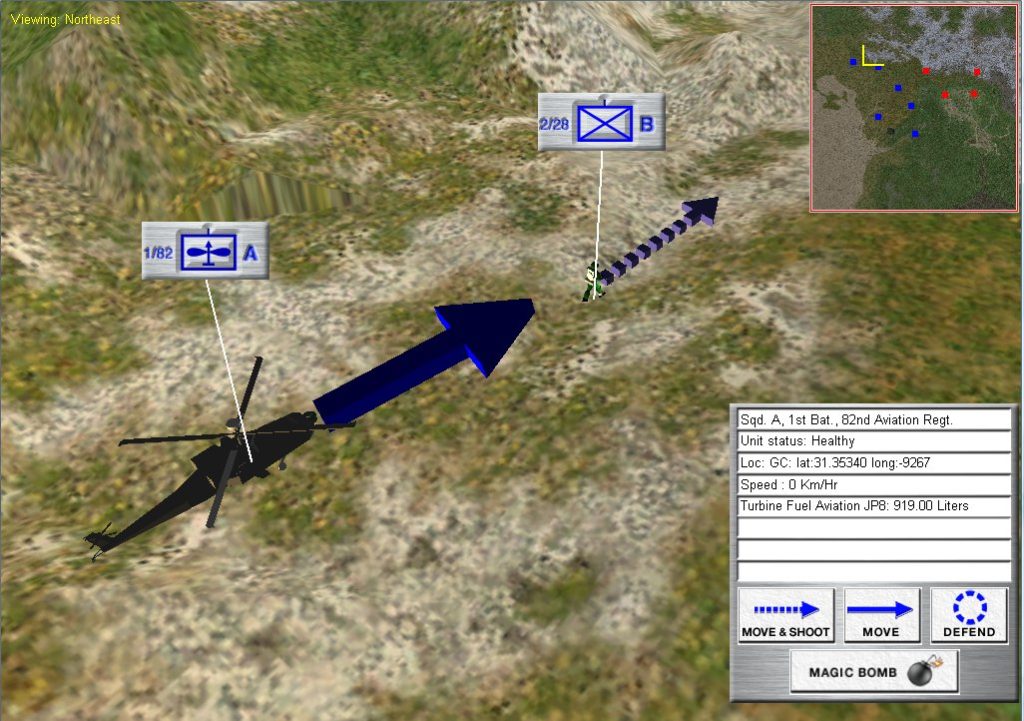

OneSAF is the “Semi Automated Forces” wargame / simulator used for training by the US Army. It relies on ‘pucksters’ (see pucksters in this blog) who are usually retired military officers who make all the moves for OPFOR (Opposition Forces), MARS provided an intuitive Graphical User Interface (GUI) for the modification and running of OneSAF scenarios.

Screen capture of the MARS project for the US Army. MARS was a front end to facilitate creating and managing scenarios run on the Army’s OneSAF military simulator. The ‘Magic Bomb’ option is the puckster’s term for ‘magically’ removing a unit from the simulation. Click to enlarge.

CAPTURE: Cognitive and Physiological Testing Urban Research Environment (2010)

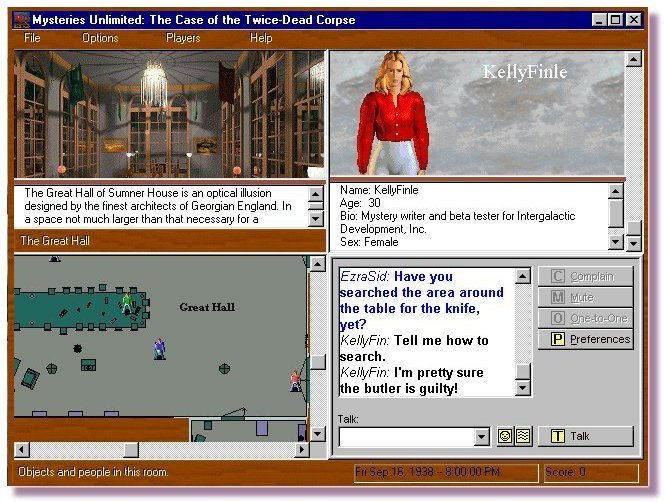

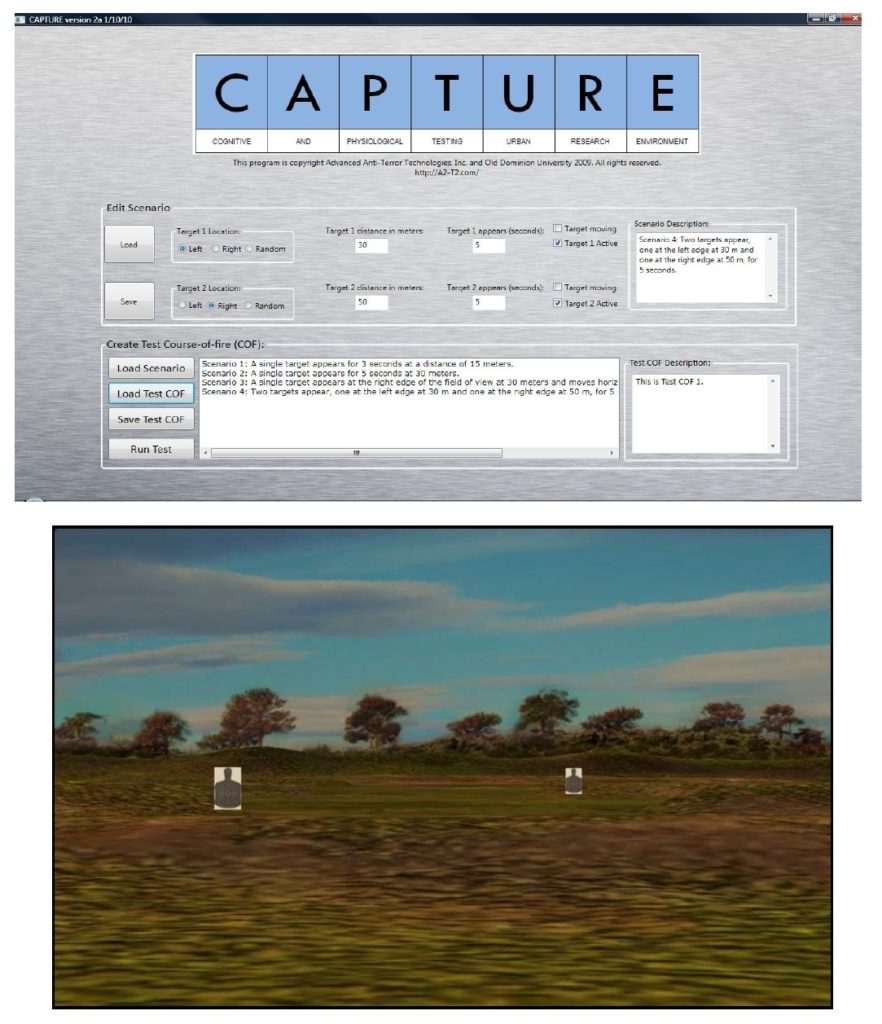

While on the surface CAPTURE appears to be a standard ‘shooting gallery’ program it was actually designed to test and store data about how returning veterans saw targets, ‘spiraled in’ on targets and reacted. There were two parts to CAPTURE: the first allowed the tester to set up any particular scenario they wanted (top image, below) and the second part (bottom image, below) was run using a projector, a large screen, an M16 air soft gun with Wii remote and laser mounted to the barrel and an IR camera. CAPTURE was done for the Office of Naval Research (Marines).

Two screens showing the CAPTURE program. The top screen shows the interface for creating target scenarios. The bottom screen is one of the the shooting ranges generated by CAPTURE. Click to enlarge.

NexGEN Behavior Composer (2011)

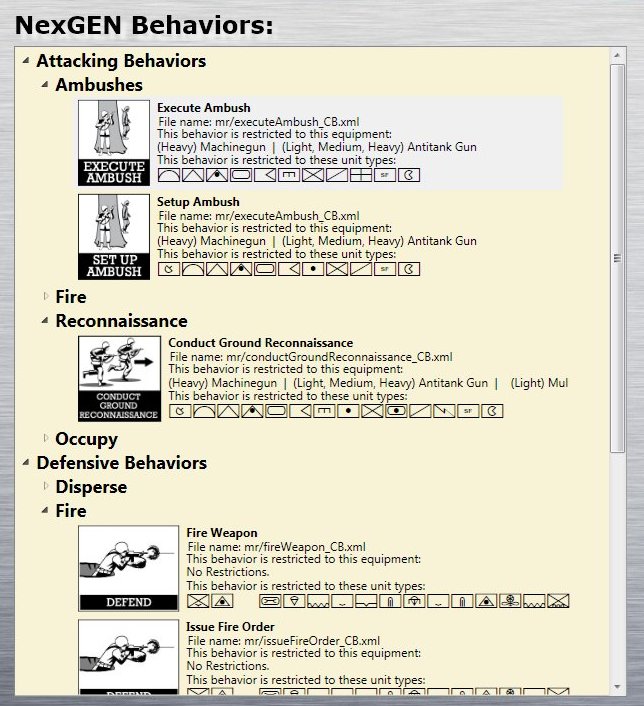

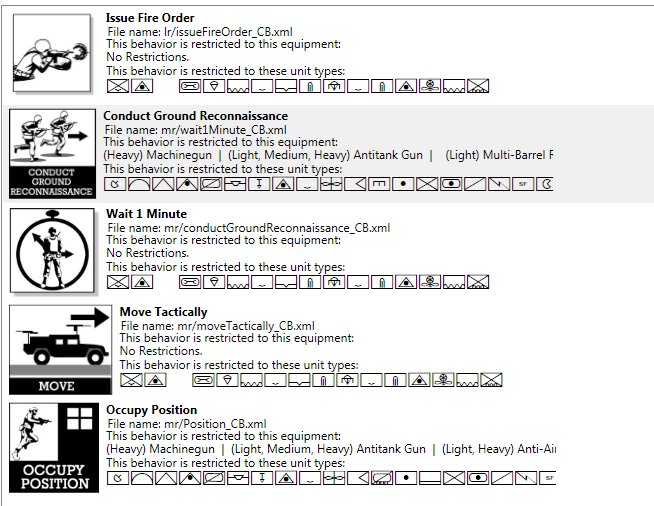

NexGEN Behavior Composer was another front-end project for OneSAF. Enemy units in OneSAF use scripted AI behavior written in XAML. These AI scripts often contained errors. NexGEN allowed the puckster to select a behavior from a hierarchical tree structure (top image, below) and click and drag it to a composing canvass where a series of behaviors could be joined together (bottom image, below). The artwork for the behaviors was done by my old friend, Ed Isenberg, who has worked with me on games since the ’80s.

Screen shot of NexGEN Behavior Composer which facilitated creating OneSAF behaviors by clicking and dragging behavior icons. This is the hierarchical tree structure of behavior primitives. Click to enlarge.

A series of behaviors have been placed together to create a complex behavior (a unit fires, conducts reconnaissance, waits for one minute, moves and then occupies a position). Click to enlarge.

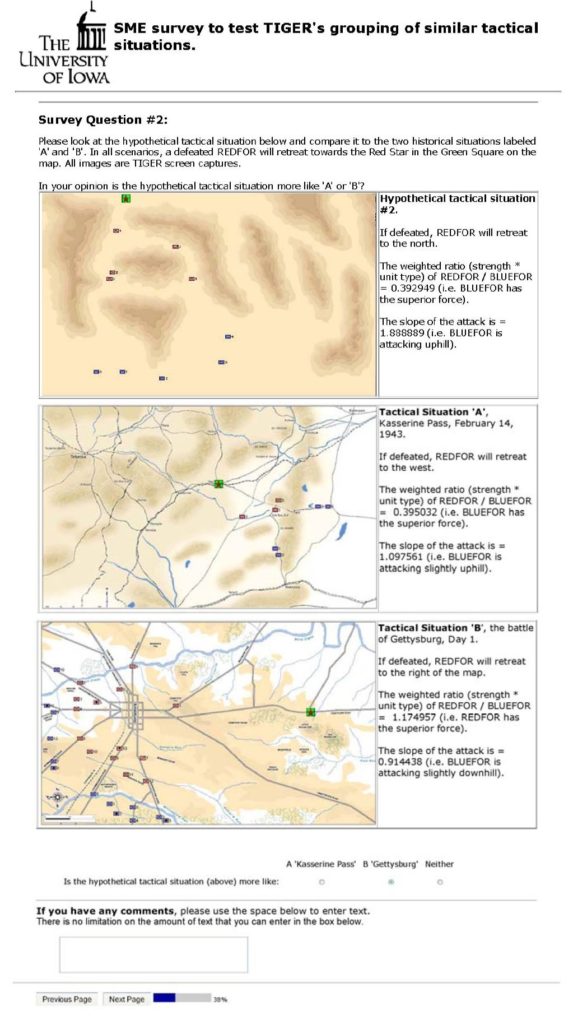

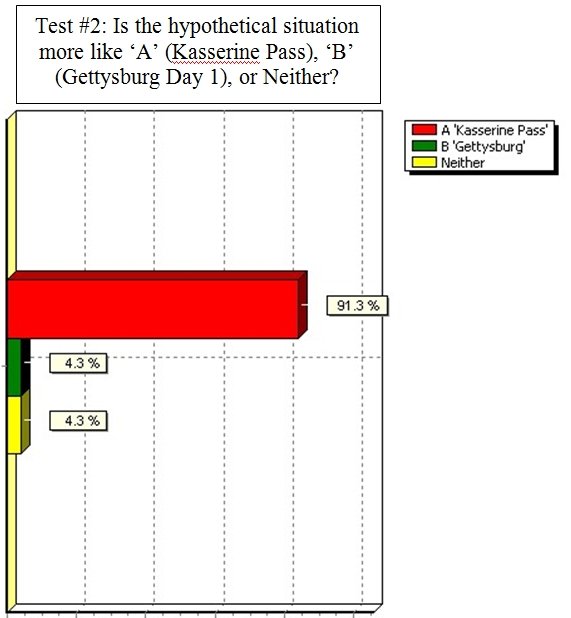

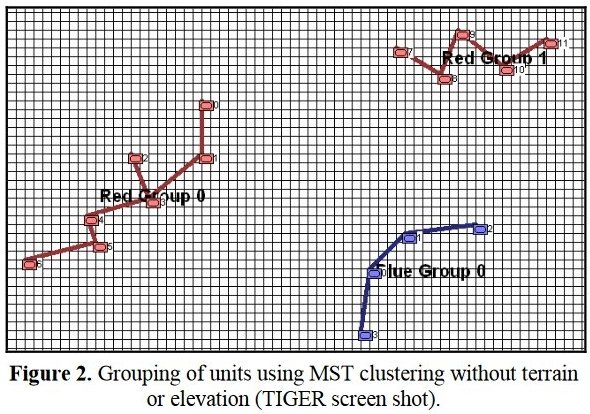

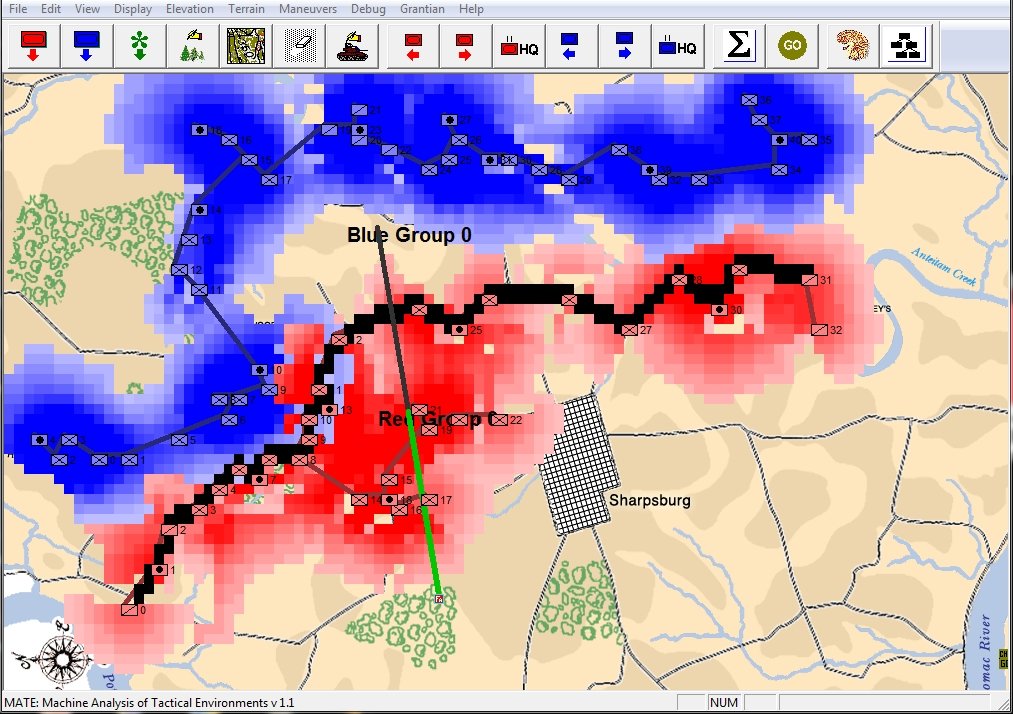

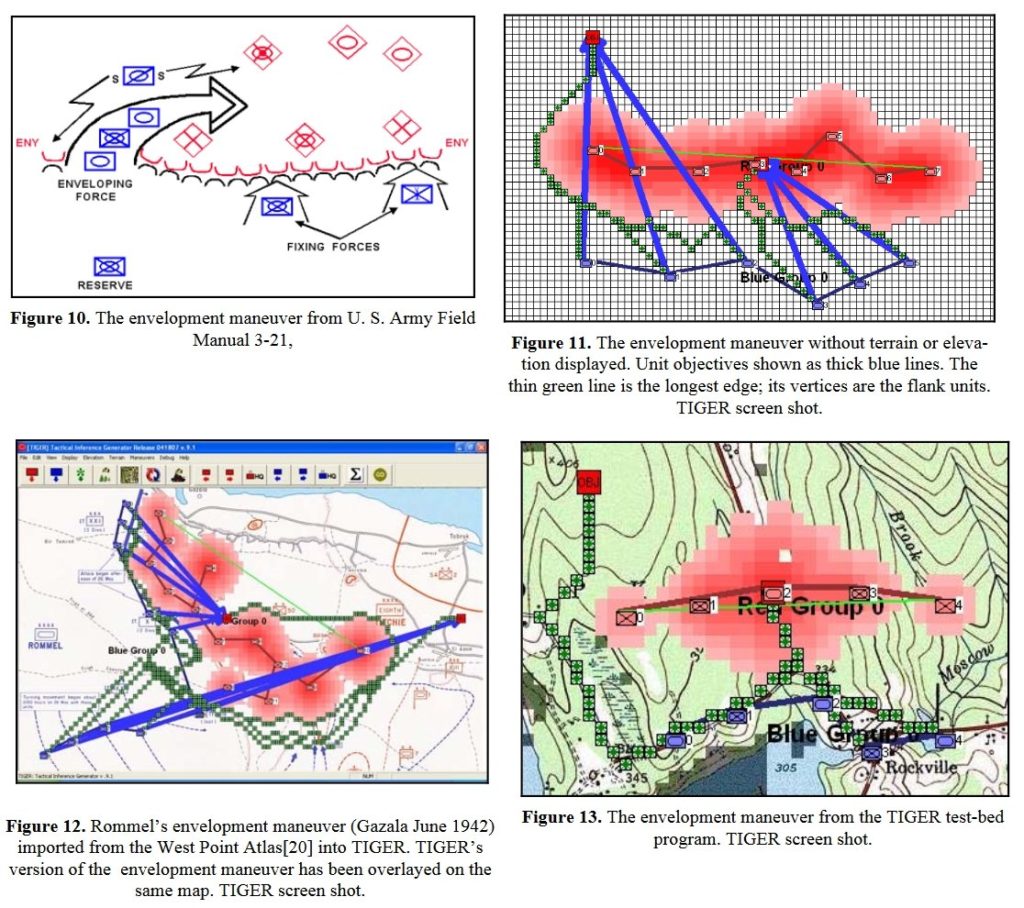

MATE: Machine Analysis of Tactical Environments (2012)

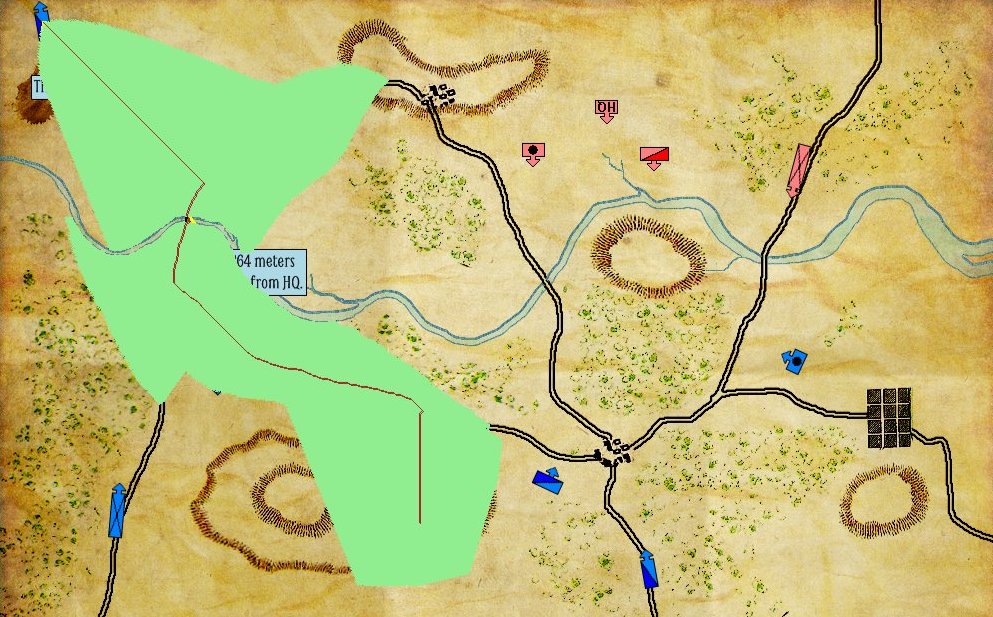

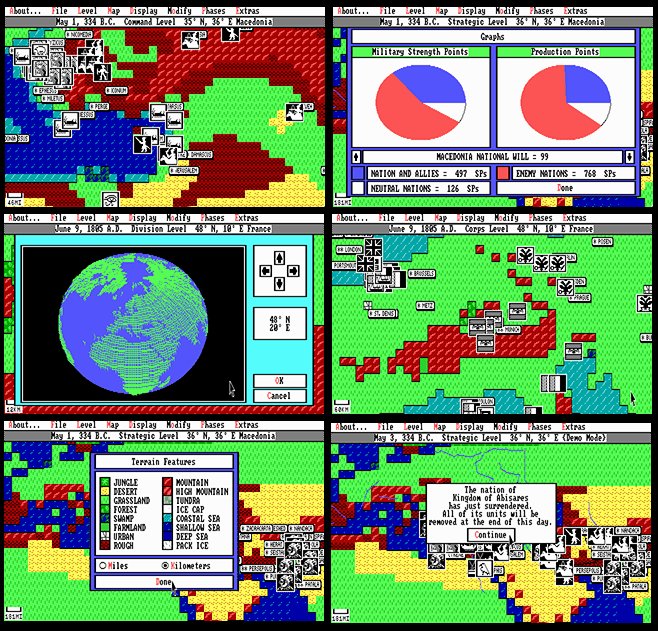

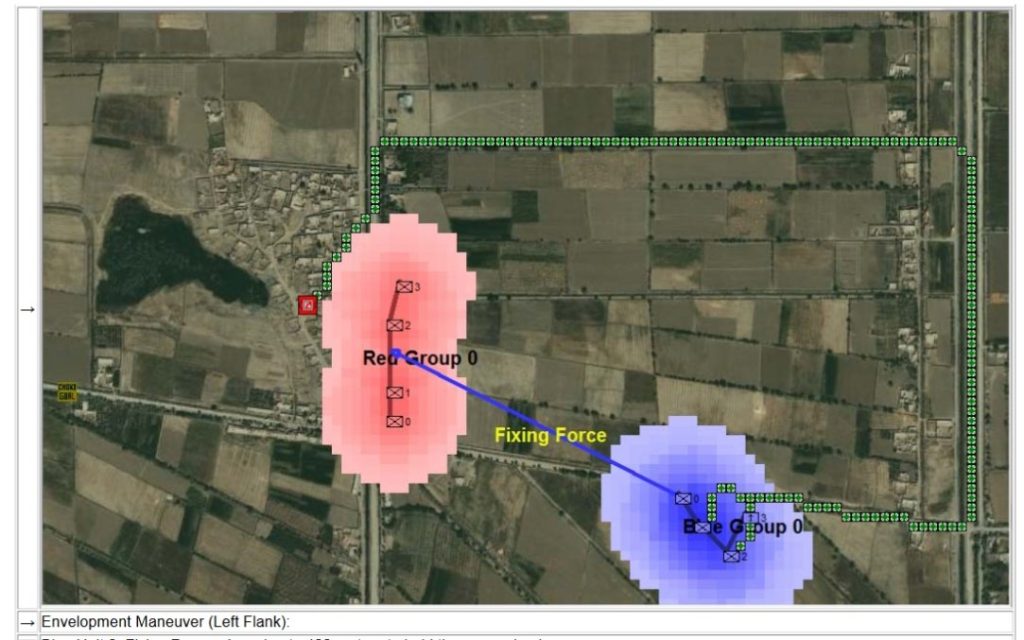

Funded by a DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Project Agency) research grant (W911NF-11-200024) MATE added a new level of battlefield analysis to the TIGER project. Building on the previous nine years of research MATE had the capability of generating a series of ‘predicate statements’ that described the battlefield and then using them to construct a hypothetical syllogism that resulted in a precise Course of Action (COA) for BLUEFOR (US forces). MATE then output this COA as an HTML file and automatically launched a browser to view the COA. MATE was designed to be available to commanders in the field via a small handheld device like a tablet. It was able to perform battlefield analysis in less than 10 seconds.

Consider this real-world situation from the Battle of Marjah:

Given the same data that the commander had in the above video MATE returned this COA (complete with unit paths and ETAs):

MATE’s analysis and COA for the Battle of Marjah: a right-flank envelopment maneuver with two infantry platoons while a fixing force of the mortar platoon and a third infantry platoon kept the enemy’s attention. Click to enlarge.

To see the entire MATE analysis and COA results for the Battle of Marjah click here. (this will load a PDF of MATE’s HTML output on a new tab).

Unfortunately, about the time that I demonstrated MATE to DARPA a series of unfortunate events occurred that were to change my life. The United States Congress passed the Sequestration Transparency Act of 2012. This resulted in a 10% across the board cut in all federal spending. DARPA seemed especially hard hit and they stopped all funding for 4CI (Command, Control, Communications, Computers and Intelligence) research. Only a few years after receiving my doctorate, specifically so I could be the Principal Investigator on government funded 4CI research, I was out of a job.

Without any research funding, and not wanting to relocate I returned to the University of Iowa as a Visiting Assistant Professor teaching Computer Game Design and CS1. I love teaching. And I am extraordinarily proud of receiving the highest student evaluations in the department of Computer Science but I didn’t have as much strength as I used to have. I found myself out of breath and exhausted after a lecture. And then my kidneys began to inexplicably fail.

In 2013, because of the efforts of superb doctors Kelly Skelly and Joel Gordon at the University of Iowa Hospital, I was diagnosed with a very rare and usually fatal blood disease, AL amyloidosis. In 2014, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, I was hospitalized for 32 days, my immune system was purposely destroyed and I received an autologous bone marrow / stem cell transplant. This was followed up by a year of chemotherapy. Being severely immunocompromised I have contracted pneumonia six times in the last two years. Now, against the odds (and I’m a guy that deals with probabilities a lot so I’m being literal) I’ve completely recovered. My kidneys and lungs are permanently damaged but I’m not going to die from this disease. But, it also means I can’t teach anymore, either.

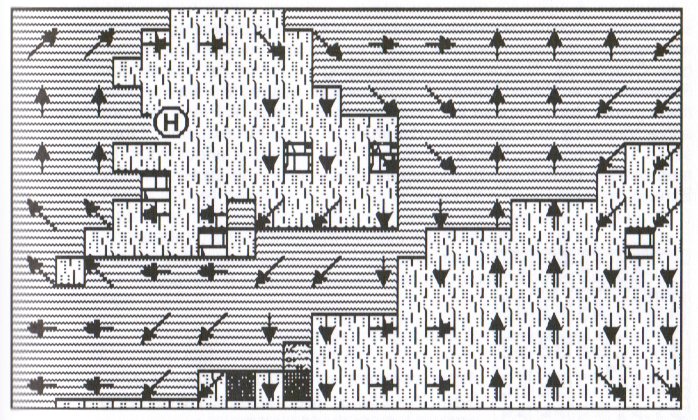

Luckily, I can still sit at a desk and write computer code. General Staff is my return to writing a commercial computer wargame and it will be the first commercial implementation of my tactical AI algorithms that I have been developing since 2003.

I need to produce a game that you grognards want. And, that means next week I will be posting a new gameplay survey to pin down exactly what features you want to see in the new game. As always, please feel free to contact me directly (click here) if you have any questions or comments.