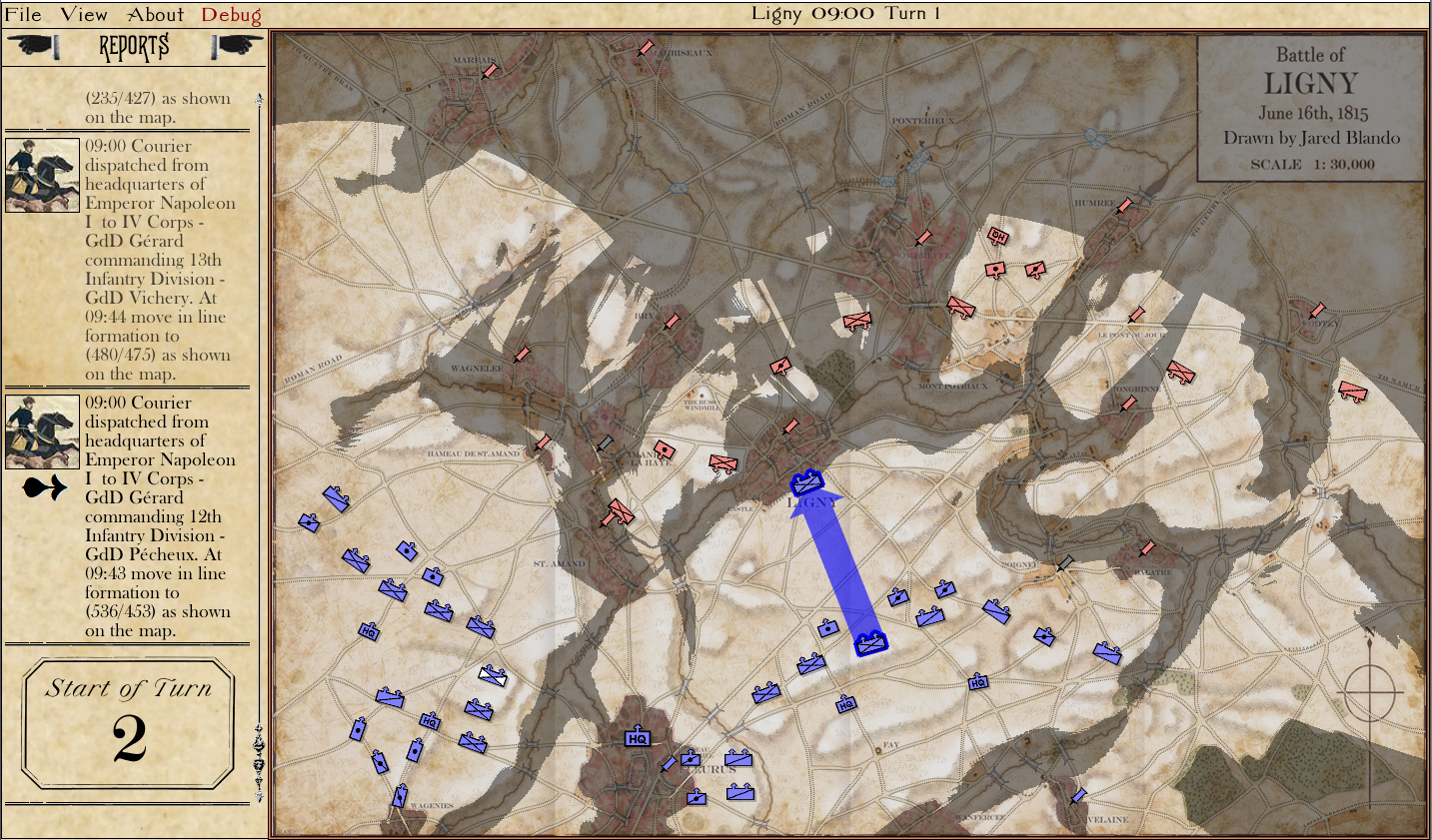

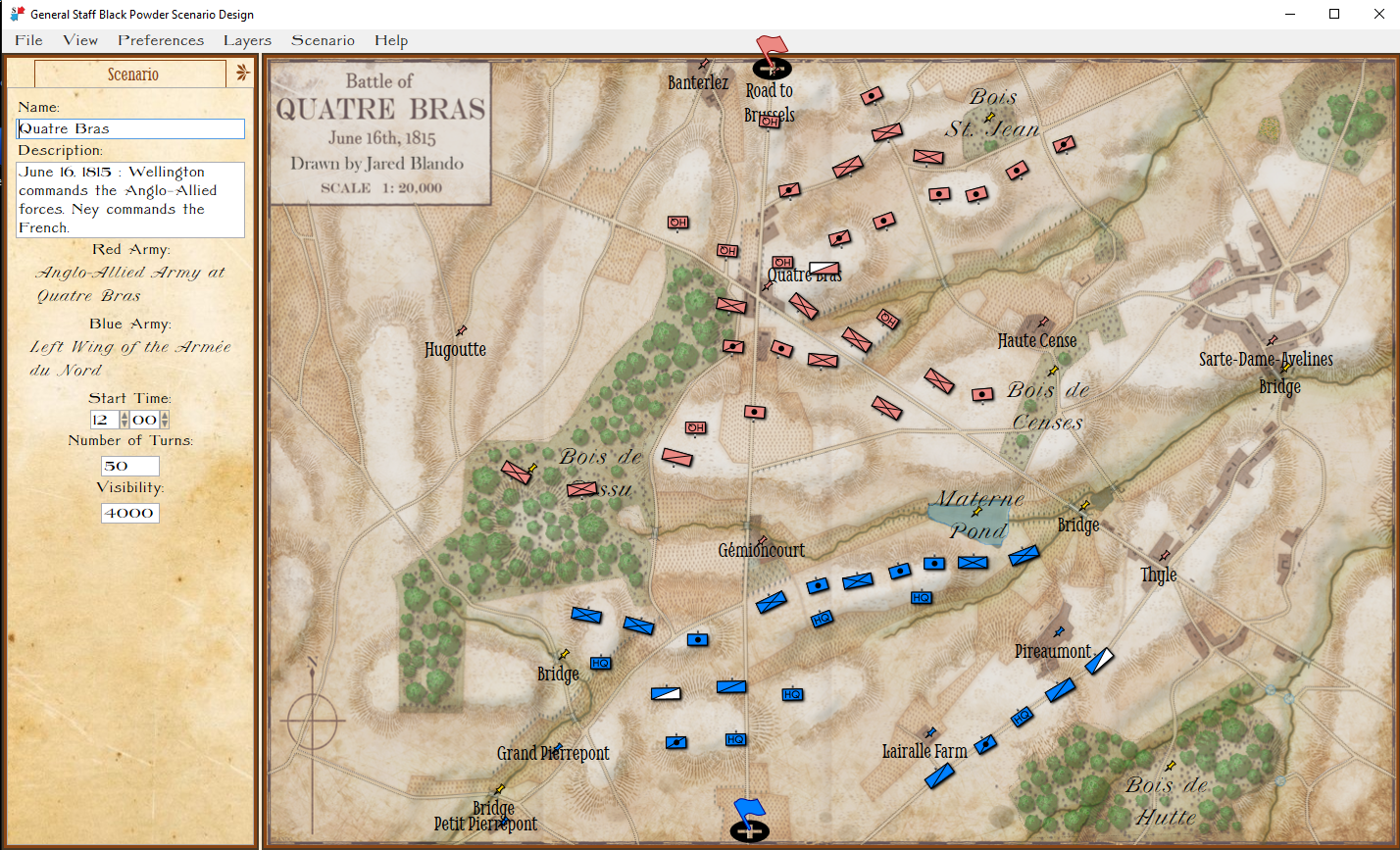

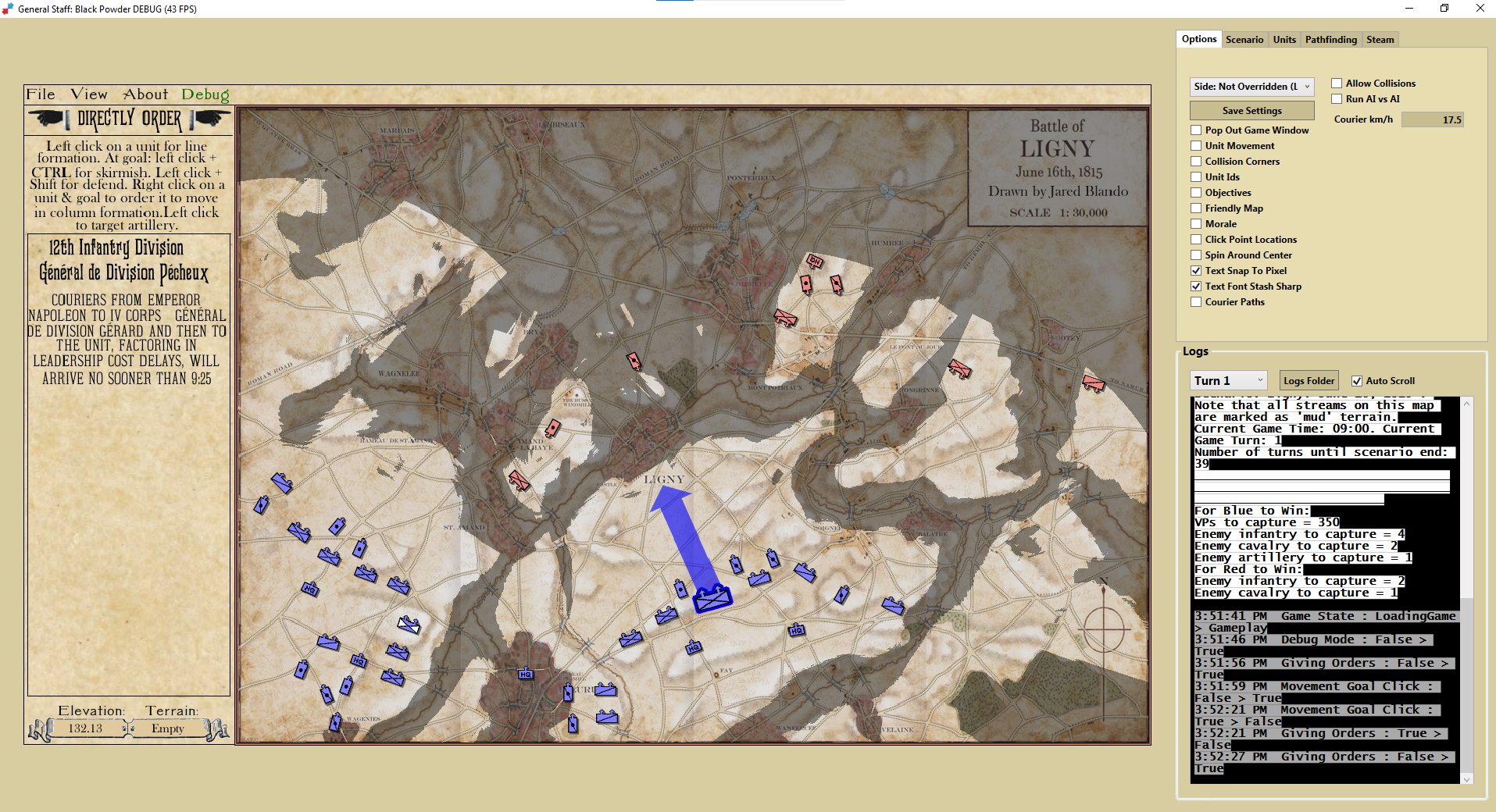

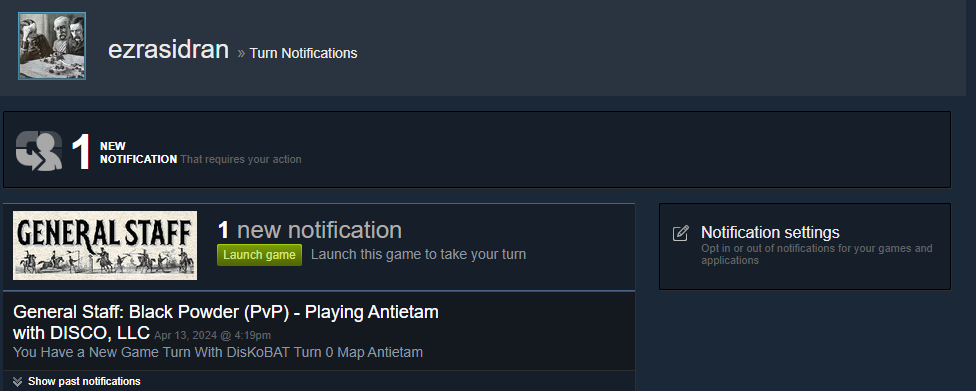

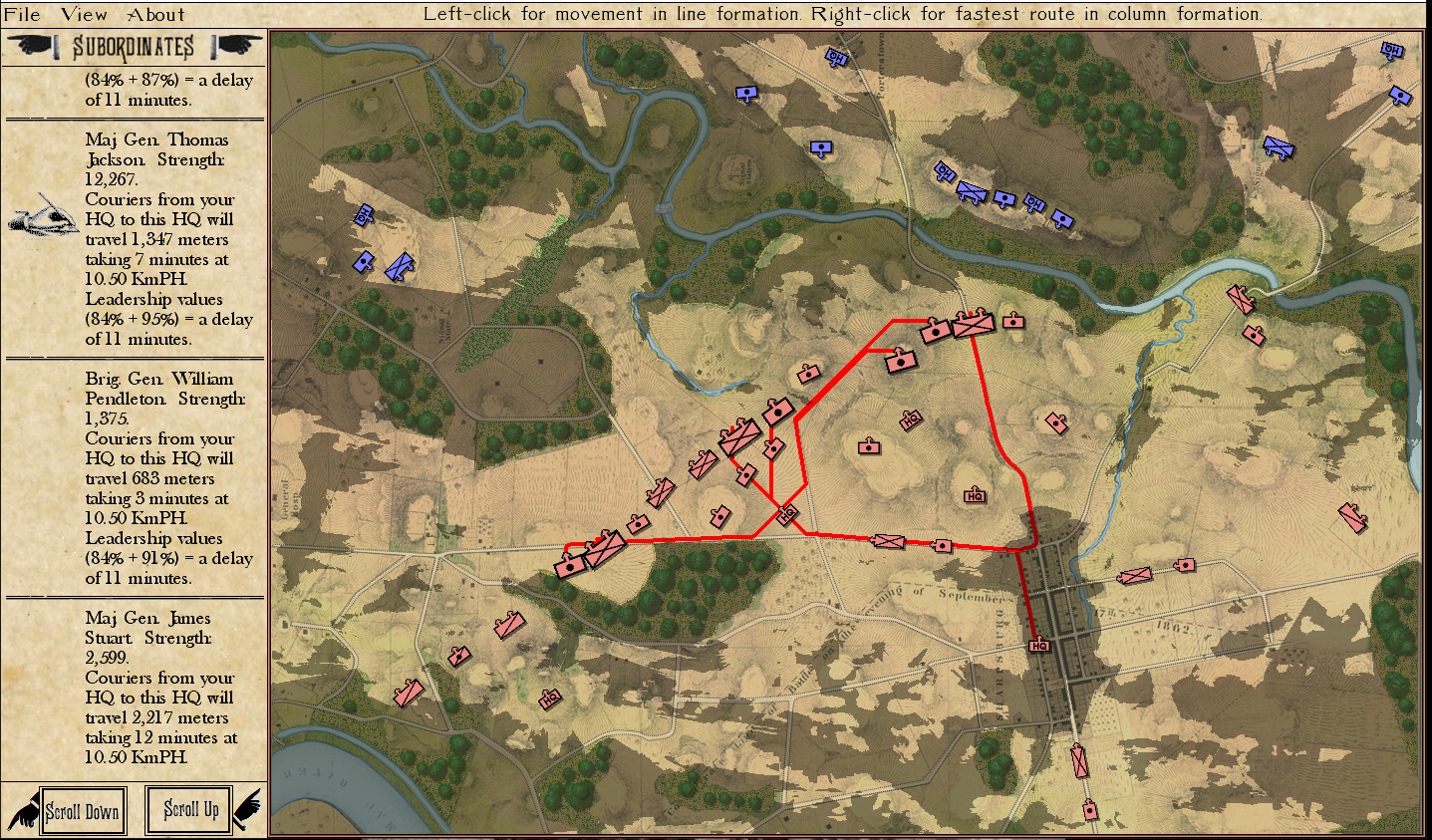

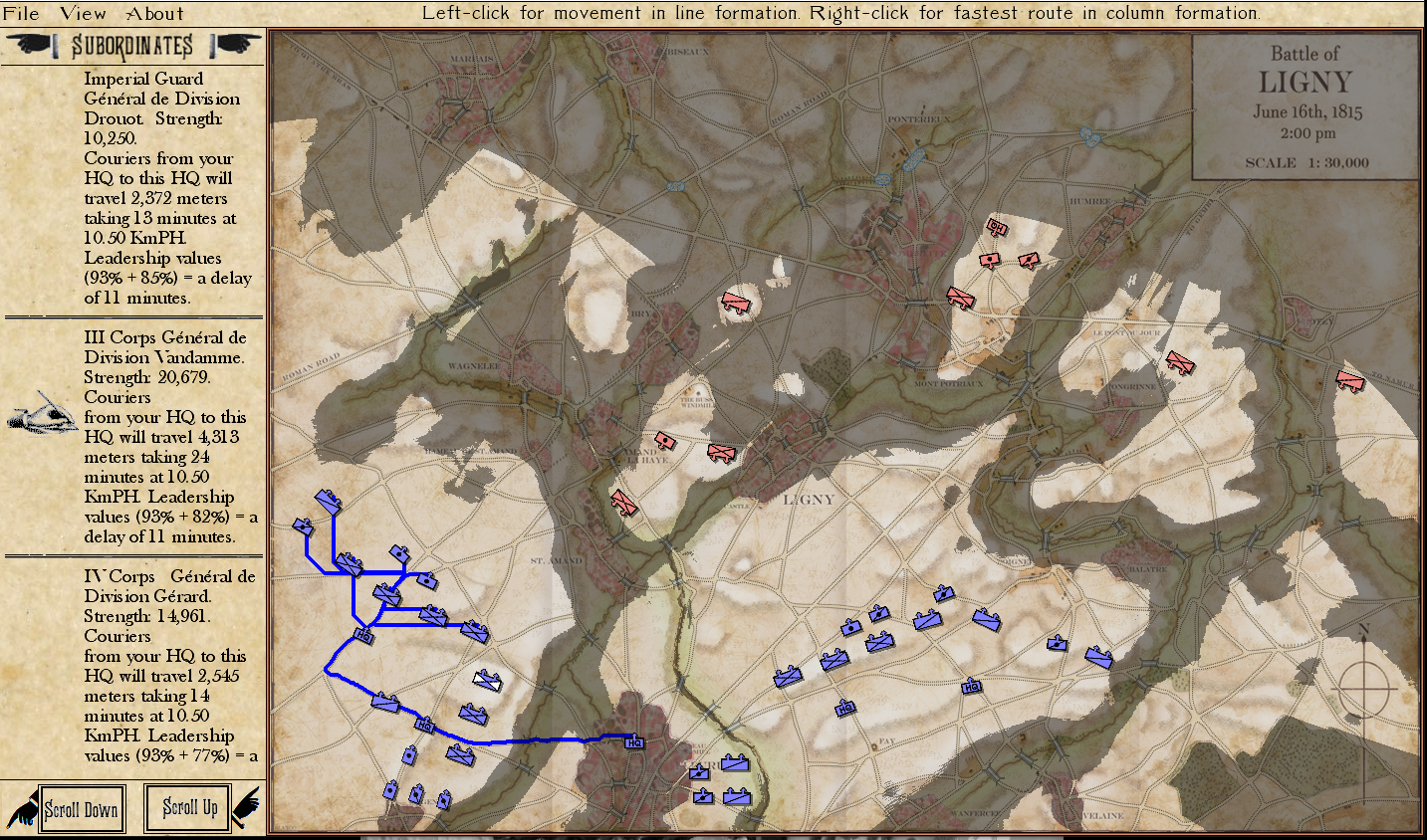

The delay in the transmittal of orders from headquarters and staff is one example of the Friction of War. Note the calculated time for couriers to arrive displayed in the Subordinate Orders list on the left of the screen. The red lines are the routes that couriers from General HQ to Corps HQ to individual units will take. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

Carl von Clausewitz, in has seminal work, On War, (Book 1, Chapter 7) originated the phrase, “Friction of War”:

Carl von Clausewitz painted by Karl Wilhelm Wach. Credit Wikipedia.

“Friction is the only conception which, in a general way, corresponds to that which distinguishes real war from war on paper. The military machine, the army and all belonging to it, is in fact simple; and appears, on this account, easy to manage. But let us reflect that no part of it is in one piece, that it is composed entirely of individuals, each of which keeps up its own friction in all directions.”

I knew that if General Staff: Black Powder were to be an accurate simulation, and not just ‘war on paper’, that the friction of war would have to be calculated into the command / orders chain. One part of this – the distance the couriers will travel from one headquarters to the next to deliver their orders and the time it takes to travel this distance – can be calculated with reasonable certainty (I’m using the rate of 10.5 kilometers per hour for a horseman, I’m not an expert but this seemed reasonable, and it’s easy to change if somebody has a more accurate value).

Another example of friction of war is factored into the delaying of the arrival of orders is Leadership Value:

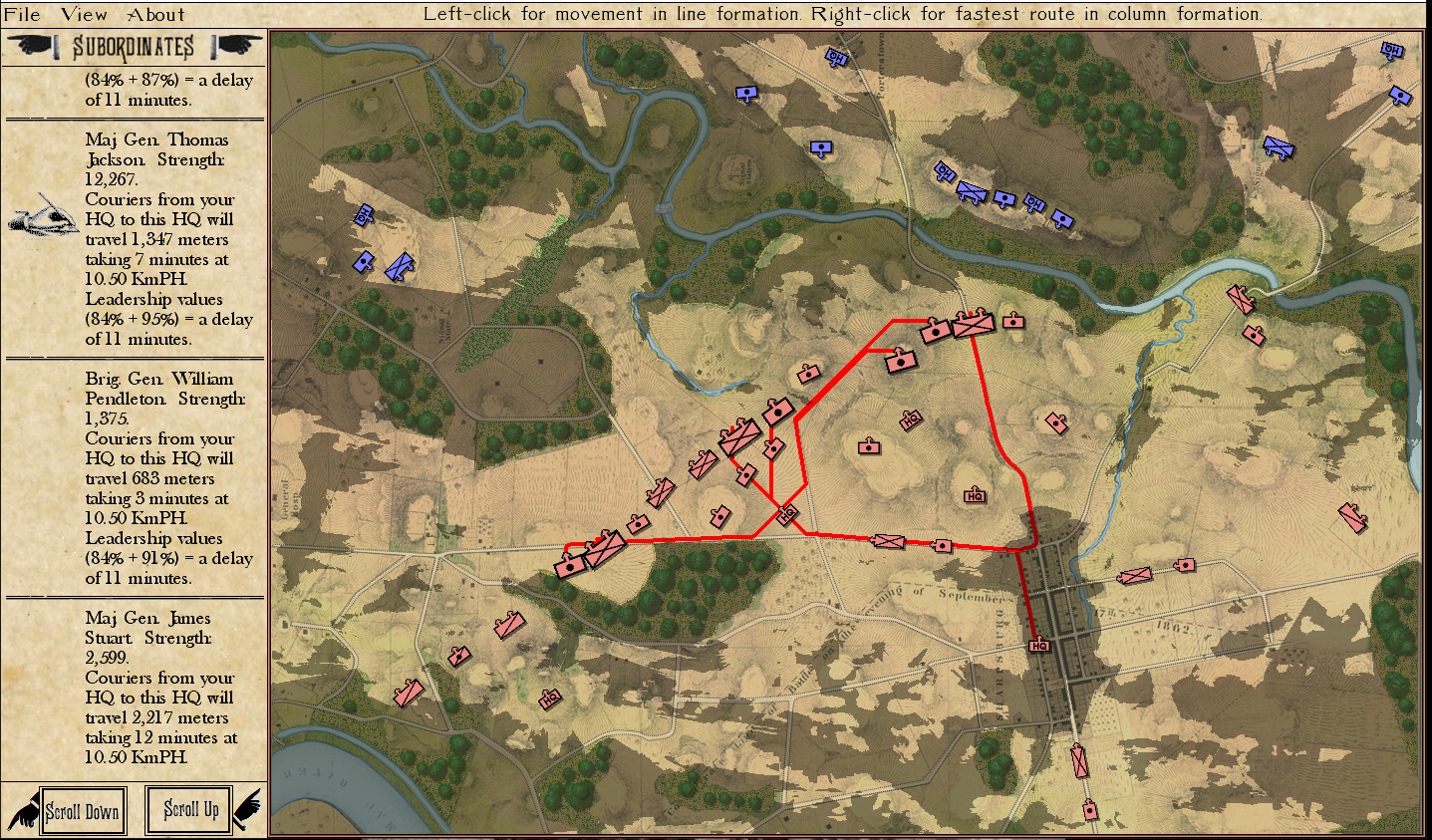

In this example, the Imperial couriers will travel over 4.3 kilometers, taking 24 minutes, to deliver their orders. Also, note the cost of the combined Leadership Values. Because Napoleon and Vandamme have very high Leadership Values little additional delay is added. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

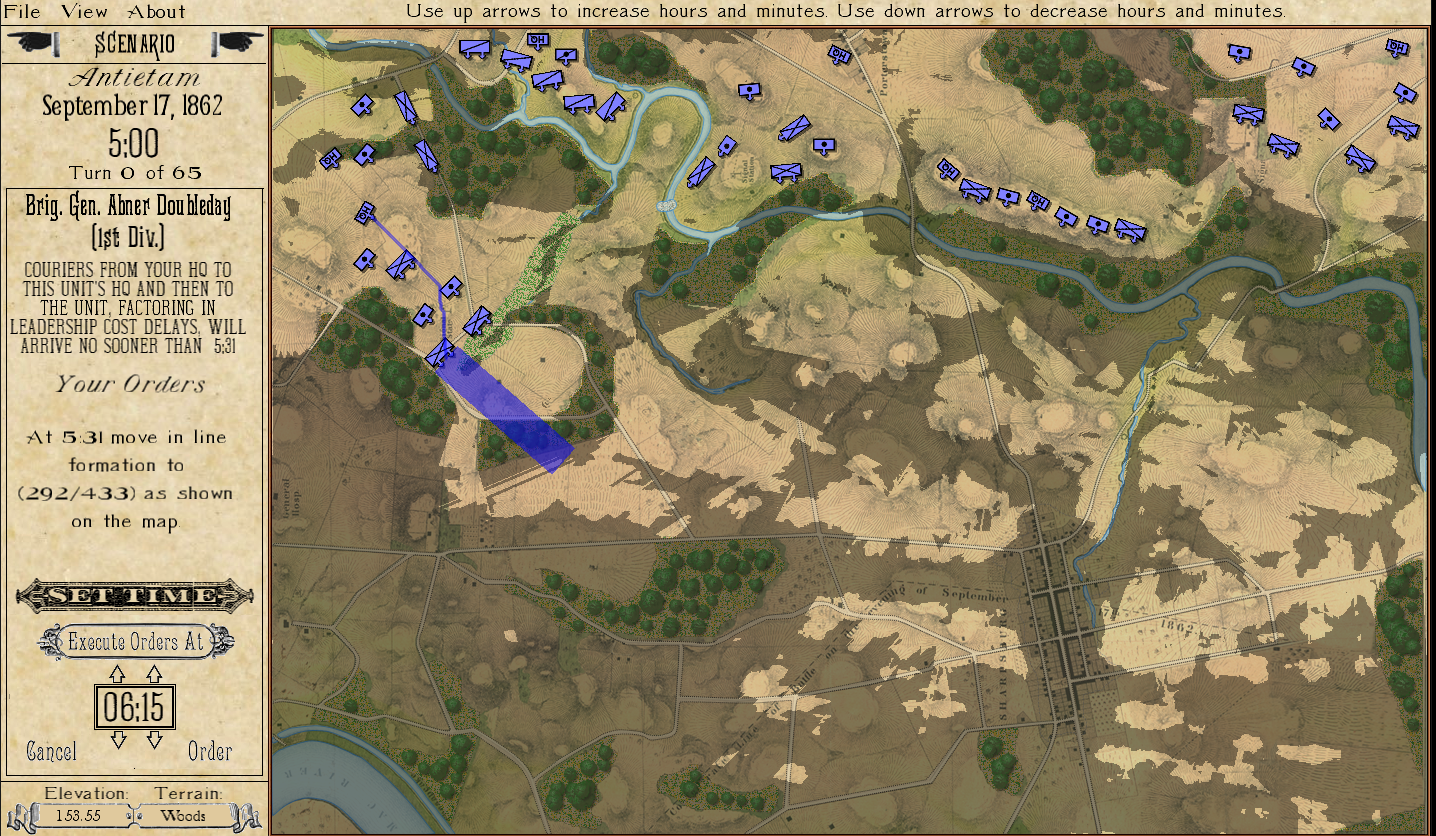

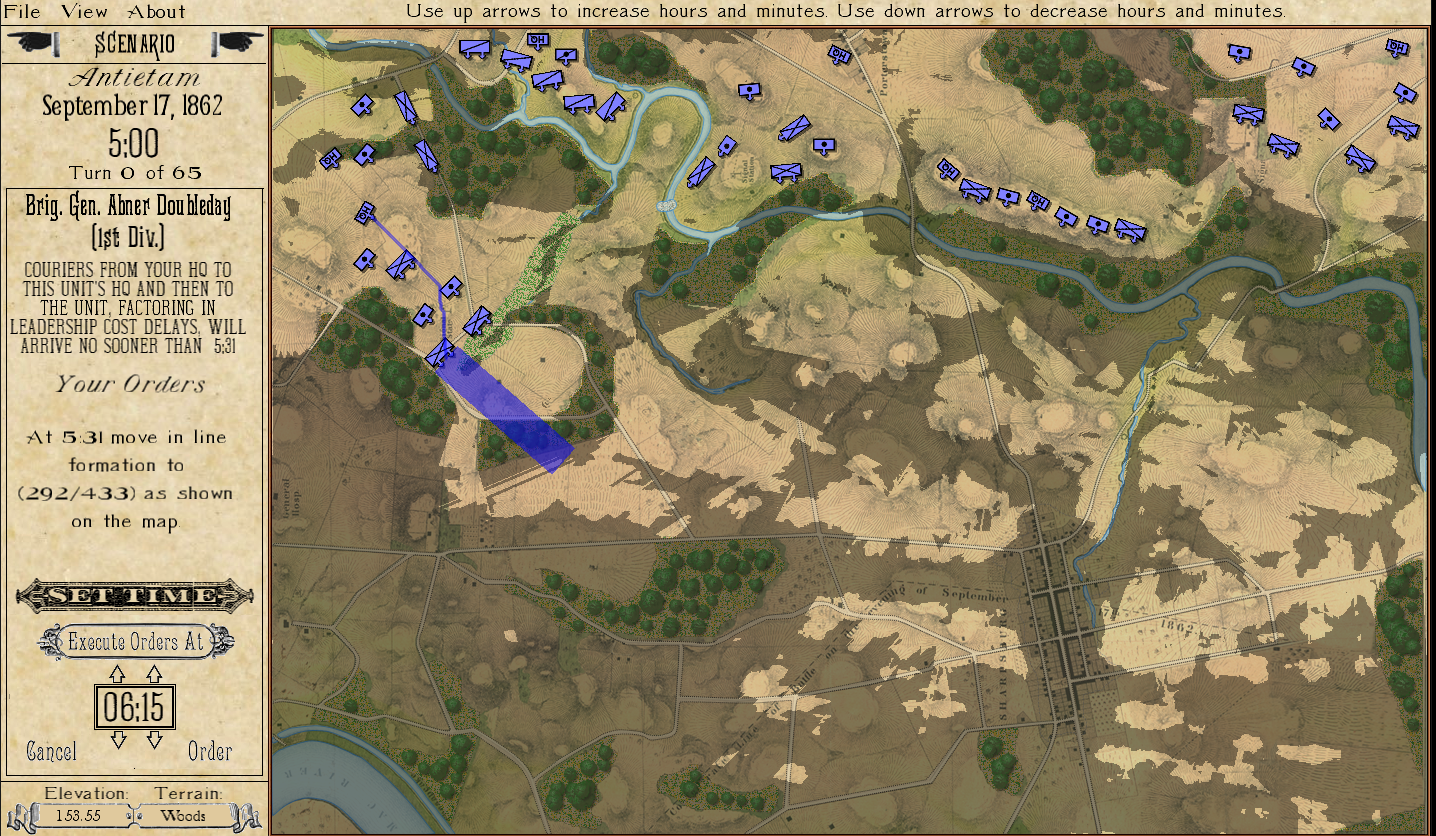

You can specify at what time the order is to be executed (in this case 6:15), however you can not set a time earlier than when the couriers would arrive. This allows for coordination of attacks across units. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

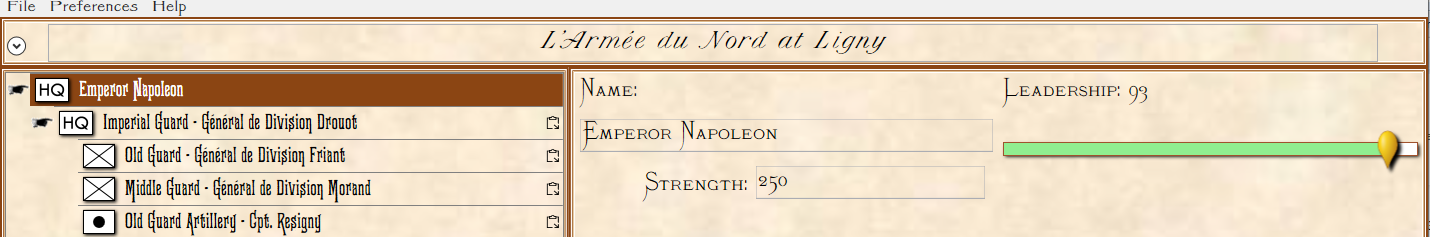

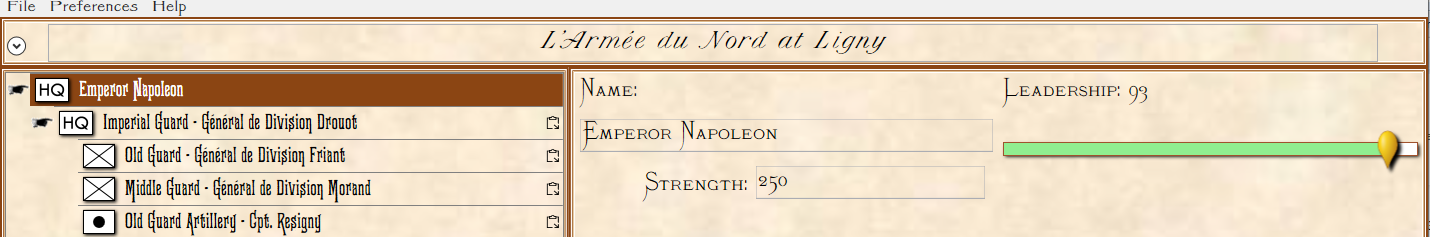

The other value – and it is arbitrarily set – is the cost of ineptitude, incompetence, lack of motivation, and sloppy staff work. In the above scenario (Ligny) Napoleon’s Leadership is set at 93%:

The slider adjusts Napoleon’s Leadership Value which effects the delay in issuing orders. General Staff: Black Powder Army Editor screen shot. Click to enlarge.

I understand that Napoleon may have been feeling a bit under the weather during the Hundred Days Campaign. You can set his Leadership Value to anything you want in the Army Editor (above).

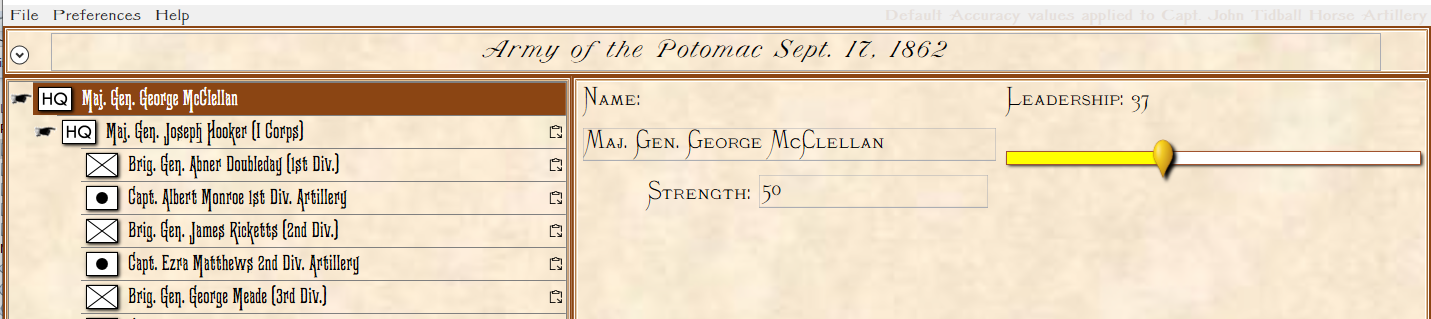

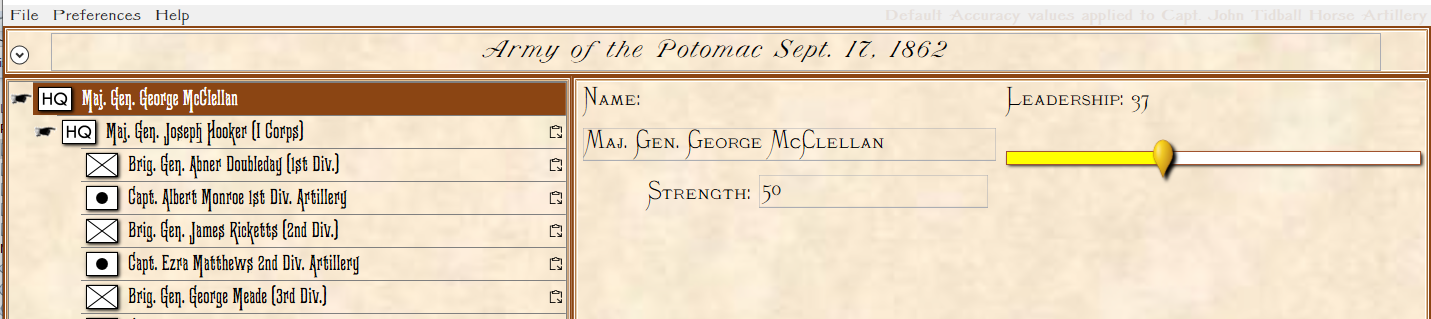

Major General George B. McClellan’s Leadership Value can be changed in the Army Editor. Click to enlarge.

Did I set McClellan’s Leadership Value too low? He was amazingly incompetent. Note below:

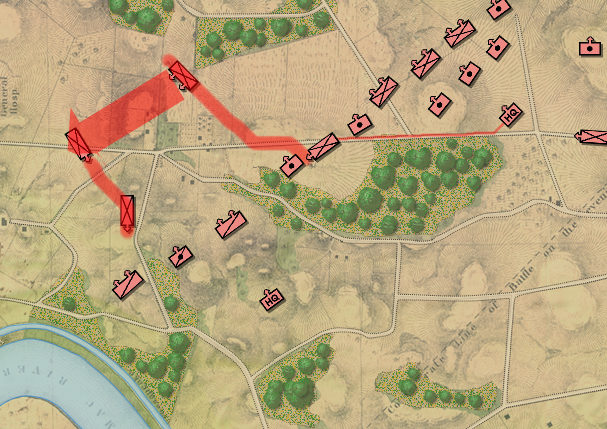

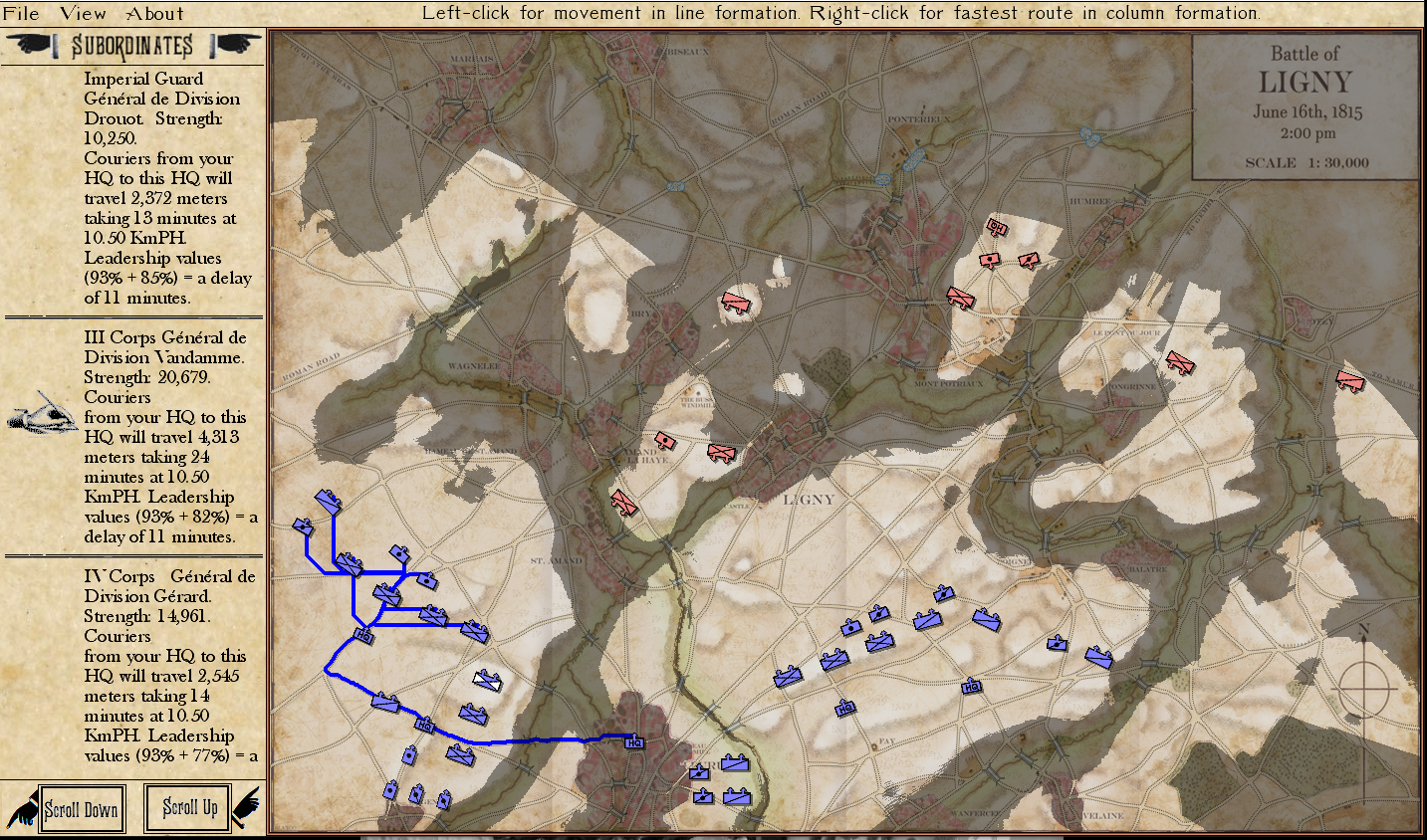

The combination of McClellan’s and Burnside’s extremely low Leadership Values adds an additional 29 minutes to the transmittal of orders. The blue lines trace the route that couriers would travel from McClellan’s headquarters to Burnside’s headquarters and then to each division and battery. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

The combination of McClellan’s and Ambrose Burnside’s Leadership Values results in almost a half hour delay in transmittal of the orders (remember after receipt of the orders, Burnside has to send couriers to his divisional and battery commanders, too and their Leadership Values effects the delay before their unit executes the order). After factoring the time it would take for a horseman to travel the distance between McClellan’s headquarters to Burnside’s headquarters (14 minutes) the earliest that a unit could be expected to respond to the original order from General Headquarters would be forty-one minutes later (and, in reality, a bit after that because of that unit’s Leadership Value).

The path of the couriers from McClellan’s headquarters, to Burnside’s Headquarters and then out to the divisions and batteries. General Staff: Black Powder screen shot. Click to enlarge.

I have spent some time at Antietam and studied it at length and this delay of about three-quarters of an hour between the time McClellan wanted to issue an order and the men of Burnside’s IX Corps moved out seems if anything, too optimistic of a timetable. In fact, as I write this, I think I need to increase the penalty for poor Leadership Value. McClellan and Burnside couldn’t possibly have got units moving in less than an hour.

As I have begun playtesting General Staff: Black Powder I found the delay between issuing orders and wanting to see something move now was a bit disconcerting. It shouldn’t have been. I’ve read enough military history to know that battlefield orders were often transmitted the night before and moving units around during the battle could be a risky proposition. Some armies, however, were less afflicted with these problems than others, and that I would attribute to ‘leadership value’ which also encompasses the army’s general staff.

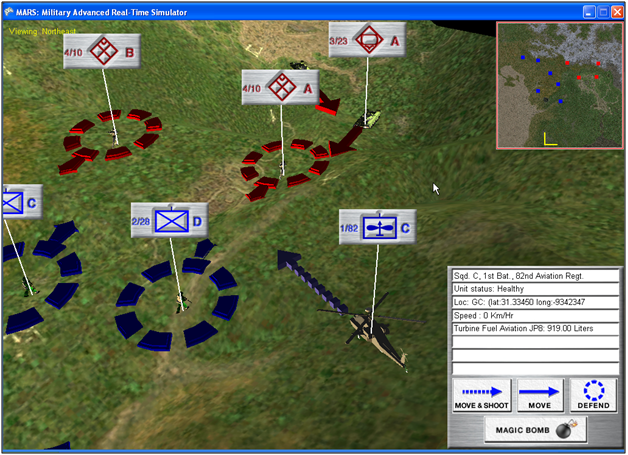

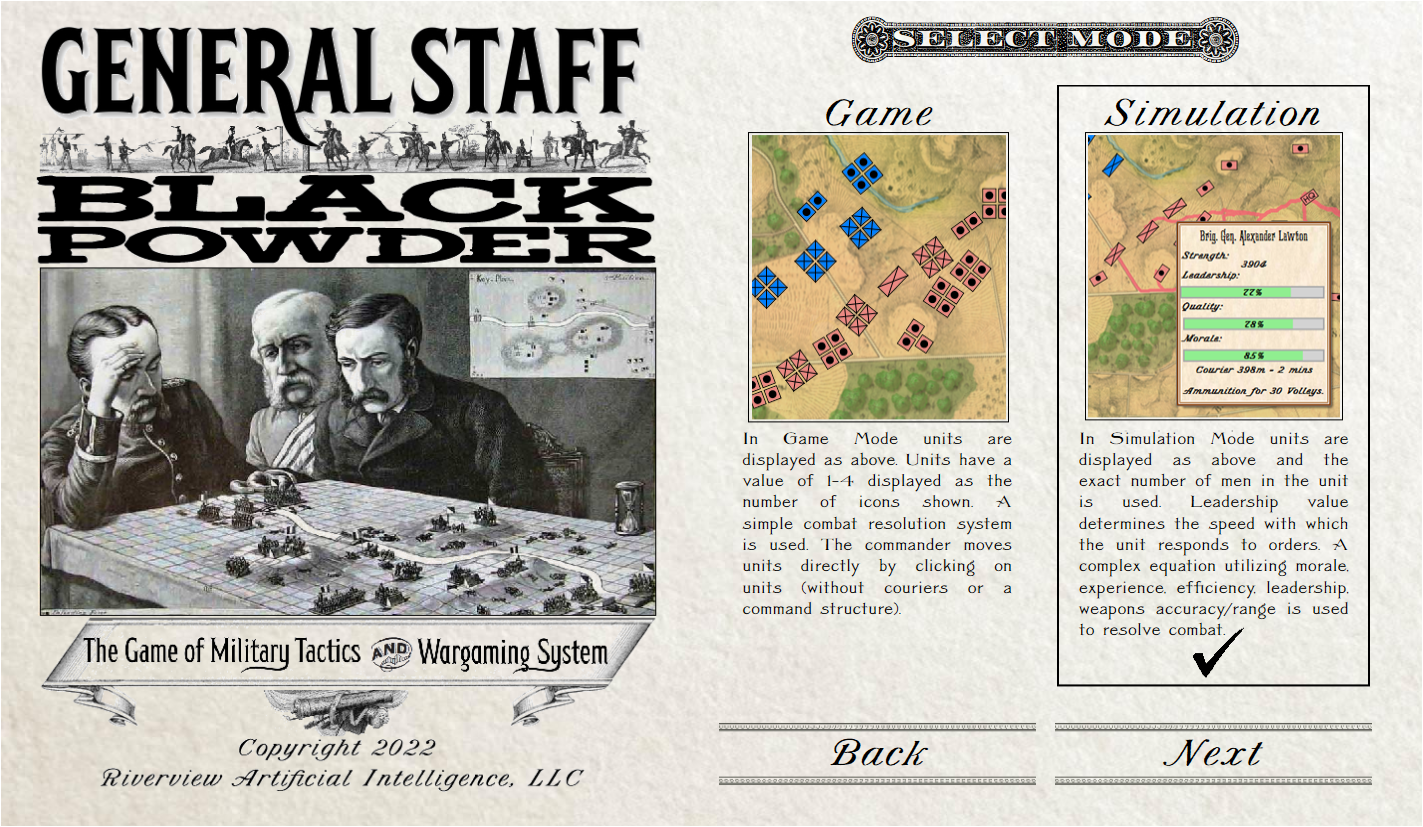

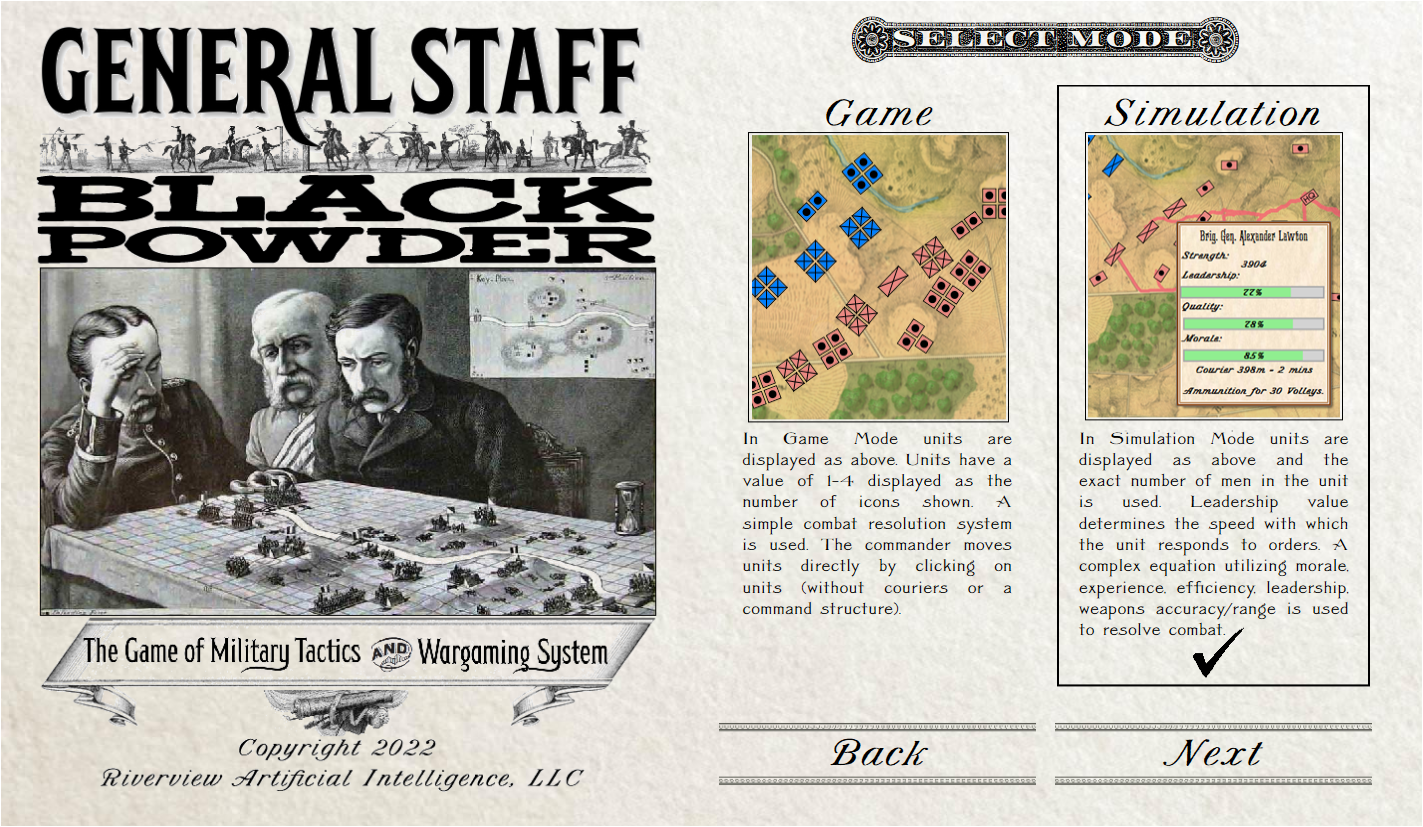

If you don’t want to use General Staff: Black Powder as a simulation that inserts a calculated delay between orders and execution, and would rather just move units instantly, there is ‘Game Mode’:

The Select Mode screen in General Staff: Black Powder. The user chooses between ‘game’ and ‘simulation’ with differences in rules and unit icons. Click to enlarge.

Game Mode has the same maps but uses simpler icons and rules. I originally envisioned Game Mode as a way of introducing wargaming to a new generation (I wanted to write it for the XBox). Anyway, it’s included with General Staff: Black Powder.

Lastly, I know everybody is waiting for news about when can I get my hands on the game?!!?!! My friend, Damien, wasn’t able to work on finishing it using Unity so I’m finishing it up using MonoGame. As you can see I’m pretty far along and I think I will be playing the first ‘actual game’ (that is a simulation from start to finish) within the next couple of weeks; maybe sooner. After that, probably at least another month of fixing bugs, but then I’m hoping to set up a Beta download for all the early backers via Steam. We have a space on Steam but I haven’t even begun to build it out. Obviously, I’m just one guy, I’m working as fast as I can, but I think this is all good news. Also, I’m working on a video to show everything off.

As always, if you have any questions or comments, please feel free to contact me directly.